What makes a good bug report?

Background: This started out as a document I wrote at Angie’s List when first learning how to test / debug / write bug reports without looking like an idiot to the engineers I was working with. I’ve updated it multiple times at Dispatch and am copy + pasting it here (with emojis and all).

Reporting an Issue

- Instead of posting in Slack or a channel like #production-bugs, create a ticket in Jira. This is to ensure the 🏀 isn’t lost in an ephemeral chat conversation.

- Discussion will occur on the ticket itself (not in Slack), so they are not lost when the time comes to work on this issue.

- This ensures the 🏀 isn’t dropped if there are multiple issues going on at once.

- We don’t have multiple people jumping in to try and triage.

- Bystanders can better track what’s going on with a specific issue and not need to ask for an update.

Why the details matter

The more accurate and more detailed your submissions are, the faster we (product, engineering, QA) can re-create the bug and come to a speedy resolution. We are all working under time constants and competing priorities, so the faster we can understand what the problem is, where it’s occurring, how to recreate it and who it affects, the faster we can resolve it.

Write a good title

Understand the audience for the bug report. There are lots of people who may read the bugs you submit: QA, PM’s, Engineers, Pro Services, Management, etc. - You have to assume that the person who reads your bug title does not know anything about what you are trying to do.

Most of your bug titles must be short, concise and must have enough information so that the user who is reading it can understand what the bug is about. Don’t write “It does not work!!!” on the bug title. That gives no information as to what is wrong, or why it’s wrong.

Down the road, a well written title can also serve as a reminder of the bug content when you are viewing a report and looking back on lists of bugs. This also helps for searching for previous bugs in issue tracking software like Jira.

A good bug title will summarize the core problem. A well written title can also hook the reader into opening the bug before others and reading its details. Remember that at some point someone is going to be triaging the bugs you log and deciding where they fit in the plan for coming sprints. A well written title helps ensure your bug gets addressed first!

An example of an unclear bug title is “The webpage does not load”. You can make this bug title better by using “HTTP 404 error when I access http://”

As you can see, writing clear bug titles that “get to the point” allow users (whomever they be) to understand the nature of the bug without even going into the bug details.

Provide background details (software / hardware details)

The key pieces of information to try to provide are:

- Environment (production, staging, etc.)

- Credentials you are using (if you are the one who is having the issue). Note: it’s preferable to create fresh accounts rather often. We have some old accounts with bad data that should not be used for testing. If a user is reporting a bug, please include their user_id.

- Browser [e.g. Chrome Version 50.0.2661.94 (64-bit)] or Device (e.g. iPhone 5, Samsung Galaxy S4)

- OS Version. Together with the device, we can spin up the exact (virtual) device used to encounter this bug.

- App version.

The Exact Steps to Recreate the Bug

The same assumption that the person who reads is reading your bug report does not know anything about what you are doing applies to the details of the bug report.

It’s important to try to find out a relatively minimal set of steps to reproduce the problem and to note them in the bug report. Giving the exact steps gives the engineer, PM, QA, etc. a fighting chance of seeing what you are seeing, and actually getting it fixed quickly.

If you can, avoid steps that don’t matter - those which have nothing to do with reproducing the bug. Including too many steps can waste time and lead to confusion. Include all steps which actually seem to matter. Write them in a clear style, in a manner which avoids guesswork.

Expected vs Actual

After showing the steps to recreate the bug, make sure you include what you expected to happen and what actually happened after taking the steps to explain how to recreate the bug.

If you observed an error message, include the exact text (or screenshot).

Sometimes what you expect to happen isn’t the built functionality and is (best case scenario) a feature request or (worst case scenario) bad UX design.

Additional pieces of helpful information 👇

THERE IS NO BETTER TIME THAN RIGHT NOW WHEN YOU ARE EXPERIENCING THE PROBLEM TO DEBUG WHAT IS GOING ON.

If you can, grab an engineer who isn’t busy to sit with you. You can get started helping to debug where the problem is by starting with the checklist below - since these are the questions an engineer will ask when trying to figure out where the problem is occurring.

1/ Screenshots / videos

Screenshots and videos help to observe what’s going on.

CloudApp is a tool that I could not live without to quickly capture screenshots, videos and GIF’s and automatically upload to the ☁️ while copying the link to your clipboard. You can then quickly embed these issues in the description of your ticket.

If you are shooting a video or taking a screenshot, please make sure to include the url of the page in what you are recording.

2/ Check the console

If you are using the web version of one of our apps, check the console to see if there is an error there.

There’s a difference between saying “clicking complete this button doesn’t work” and checking the console and copy + pasting the error message. We can much more quickly know where to look (and fix the problem) with this additional information.

`{"errors":{"status":["cannot be changed. Some appointments are not finished."]}}`

3/ Verify the data creation

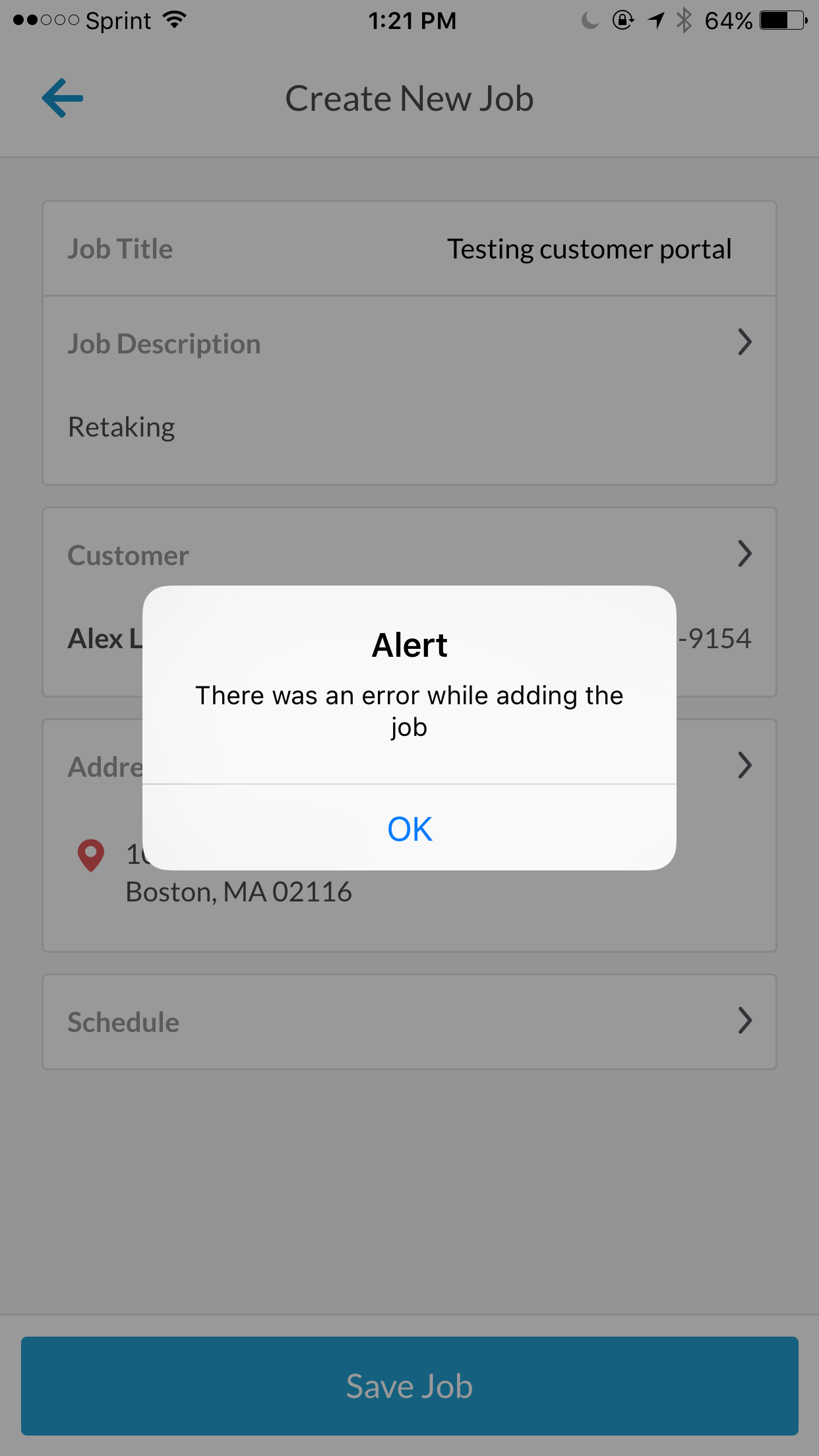

When you see an error, that doesn’t always indicate the action failed. Sometimes the action you took still succeeded. An example of that is the screenshot below when attempting to create a new job on an older version of our mobile app. While an error is shown, the job is still created in the database.

You can verify the data creation in the database or via the API.

4/ FullStory Session

If this is an issue reported by a user, try to find the FullStory session. This allows us to obseve the exact steps the user took.

This gets more helpful as FullStory adds more debugging tools and proactively finding device / browser information from our analytics tools to hone in on the problem.

5/ Check Production

If you are testing on dev / staging / sandbox and run into a problem, check production also. Is this this a regression in functionality that we have introduced? Or something that already exists in production?

6/ Make sure the code you neeed is where you expect it to be

- Sometimes an engineer gets too eager asking someone to test and asks you to test before an RC branch is merged, deployed, etc. into an environment.

- Sometimes an auto-deploy fails.

You can quickly check the commits into an environment branch (like staging) in Github or finding the build you need in TravisCI.

7/ Check configs and feature toggles

If you expect something to happen that didn’t, you can always check our configs. We use a lot of configs and feature toggles to control to deploy WIP features off, slow roll turning on a new feature for only a small percentage of users and configs to customize our app experienes.

It is sometimes inconsistent between environments - or someone else has updated a config for testing.

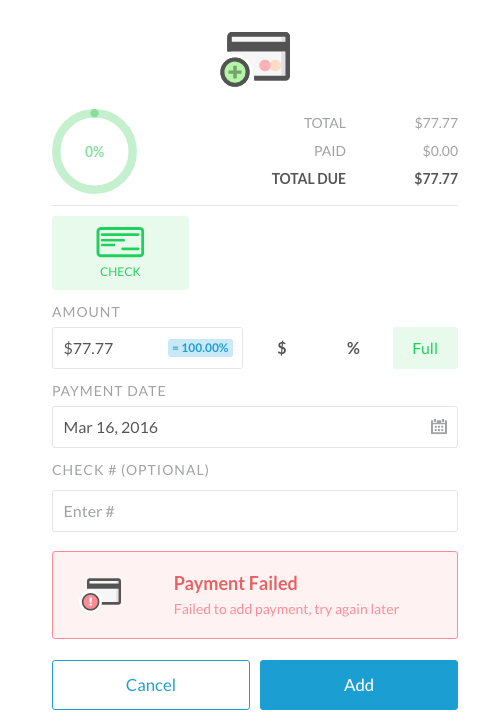

8/ Check the logs + crash logs

e.g. if I see a payment failed in the UI for a credit card payment, I can check the logs to see if it’s failing on the backend or the frontend. It’s much easier to search now than down the road and trying to use a query like “-3d” to find the specific point in time in the Loggly logs.

Similarly, if I am reporting a crash in the mobile app, the best time to find the crash in the crash logs is immediately.

Summary / Closing Remarks

The best testers aren’t the ones who find the most bugs or spend the most time testing. The best testers rapidly ship the highest quality working software to our end users and can give assessments on risk. However, bear in mind that not every bug is fully reproducible.

Closing Out Bugs

When a bug is resolved, it gets assigned back to the person who wrote the initial bug ticket to accept the work. This is a crucial point. A bug does not go away just because a engineer thinks it should.

Only the person who saw the bug can really be sure that what they saw is fixed.

But I already know how to write a bug ticket…

I’m a big believer in checklists from reading this 👇. The data speaks for itself in the power of checklists.

If anything else, this document can serve as a checklist for writing bug reports.